A blog examining the plays, production and purpose of theater company The Hudson Warehouse, the underdog of theater in the park productions. Plays (The Trojan Women in June; Cyrano d' Bergerac in July; Romeo and Juliet in August) will begin at 6:30 all summer long in the shadow of the Soldiers and Sailor's monument on 89th and Riverside. Please come!

Saturday, July 10, 2010

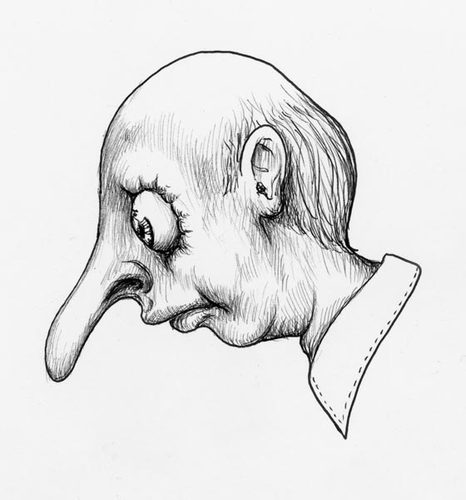

Taking Back the BIG Nose

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Three Woofs for Cyrano (Throughout the Ages)!

Shout-out!

Symmetrical braids, incredible edible legsThe play really does fit seamlessly with Talib Kweli's song, as a reference to love serenades. Kweli's whole song (see: incredible edible legs) could easily be a letter from Cyrano to Roxanne, so full it is with professions of deep-seated love. Kweli evokes Cyrano because he sees himself within the tradition of great love poets--something I don't think he's wrong to believe.

Just to track her down, I went on a ghetto crusade

Serenade this angel like Cyrano de Bergerac

The lightness of her being was unbearable (a reference to Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being)

Consider me the entity within the industry without a history

of spittin the epitome, of stupidity -- livin my life

expressin my liberty, it gotta be done properly

My name is in the middle of e-Kweli-ty

People follow me and other cats they hear him flow

And assume I'm the real one with lyrics like I'm Cyrano

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Theater Gods Bless The Hudson Warehouse

With the opening of The Hudson Warehouse's second summer show, Cyrano, less than 24 hours away, the muses have sent a sign down from above to bless our production. One actor in Cyrano,also a waiter at a neighborhood restaurant, thinks he might have seen Daryl Hannah--star of Roxanne, Steve Martin's popular 1987 movie adaptation of Cyrano--eating at said restaurant. Such a chance sighting can only signify that our production has been officially handed the torch, carried through the ages, of wonderful Cyrano productions.

The Enlightenment Comes a Century Early to Bergerac

Unlike the characters in The Trojan Women, whose uncertain historicity is discussed below, there is no doubt that a man named Cyrano lived, from 1619 to 1655. He was indeed a prolific poet, playwright and philosopher, a Gascon cadet in the Thirty Year’s War at the siege of Arras, and may have even had, as this portrait suggests, a rather large nose. Also like Rostand’s fictionalized character, the real Cyrano dreamed of going to the moon, attacked wealthy patrons and was killed by a piece of plank dropped from the sky, in all probability by a cowardly rival.

That’s about where the similarities between the real Cyrano and that of Rostand’s play—written nearly 300 years later—end. While Le Bret and Carbon are real historical figures, much of Cyrano’s relationship with them is probably invented. More essentially, the whole storyline of Roxanne (Cyrano did have a cousin, but we have no proof of feelings, or letters, between them) and Christian is almost certainly invented, as Cyrano was likely a homosexual. Furthermore, the real Cyrano lead a life of gambling and drinking, and was probably sexually active (some believe he really died of syphilis), so contrary to the sexual recluse portrayed in Rostand’s play.

Yet the most important similarity between 17th Century Cyrano and Rostand’s imagined Cyrano is, to my mind, his (their?) iconoclastic worldview. For, as both a poet and a reader of his contemporaries’ philosophies, Cyrano was one of the first believers in Enlightenment thought, which Cyrano must have attempted to meld with his more romantic, poetic ideals. According to this biography, in spite his affinity for dueling, Cyrano was fiercely opposed to the death penalty, and favored an “individualist” thinking unknown to his day. He brazenly opposed practices of the Catholic Church, and argued against the prevailing skeptics of heliocentric beliefs. Cyrano’s faith in rationalism, so rare for its time, foreshadowed the course of world intellectual history. This part of the historical man, more than anything, must have been Rostand’s truly important source material—a man before his time who held closely to his convictions.

Cyrano's Complexity

Cyrano de Bergerac—premiering tomorrow at the Hudson Warehouse—is a tough play to classify. Unlike The Trojan Women (a tragedy) or Romeo and Juliet (a romance), Rostand’s play seems part romantic-comedy, part straight satirical farce and part epic tragedy. This chameleon flavor makes the play feel disconnected at times, but—more importantly, lends the play a sense of self-awareness that augments each of its seemingly disparate moods.

Cyrano himself is particularly emblematic of this, as one of the most prismatic figures of the stage. He is at once exalted for his heroism and a parody of the tragic hero (100 warriors slain!), at once honored for his principles and a parody of self-righteousness, at once a star-crossed lover and a parody of melodrama. Yet rather than betraying an inconsistency, these ambiguities serve as one of the play’s major strengths.

The many prisms through which we can view, for instance, Cyrano, notifies the audience that the playwright recognizes both the limitations and merits of each perspective. As a simply comic figure in the mold of Don Quixote, the protagonist’s struggles would be unlikely to interest us. Yet if we were simply meant to see him as an unflawed hero, the ideal Renaissance man victimized by an inhumane society, then Cyrano would become an unbelievable character, and lose his flawed charm. These subtle middle grounds are what make Cyrano a play of such enduring value.

Saturday, June 19, 2010

Keeping the Awards Coming for The Trojan Women

When Euripides’ The Trojan Women was first presented at the city of Dionysia in 415 B.C., it won second place in a theater contest. Awards for the show have continued to this day, with our production garnering the “Pick of the Week” recognition from offoffonline.com and reviewer Kelly Aliano. Woo-hoo!

Check out her full review here: http://www.offoffonline.com/reviews.php?id=1789

--Jeff Stein

Is the Trojan Women Historical Fiction, or just Fiction?

Like countless writers before and after him, 5th-Century Athenian playwright Euripides created his story around the presumed facts of the Trojan War, as outlined by Homer. Euripides, like all the ancient Greeks, accepted both the events and personalities of the Trojan War, hundreds of years before Euripides’ time, as historical fact. His play about the imagined female victims of the war was not simply taken as a parable, or myth, but the staged, admittedly dramatized, portrayal of real events.

But was Euripides right to believe he was writing about the lives of real women? Historians have long debated the veracity of the Trojan War, with many in the modern era believing the story to be nothing more than an elaborate legend. By the late 19th-Century, indeed, it was generally assumed that “Troy” had never even existed.

Yet groundbreaking archeology from 1870 to the present day has reversed that picture. As recently as 2001, a geologist from the University of Delaware announced new findings corroborating many of the details found in Homer. After centuries of being dismissed, “it is now more likely than not” that there were “several armed conflicts in and around Troy at the end of the Late Bronze Age,” according to Archeology.org.

Does that mean there was a war started by a beauty named Helen, or that a mother named Hecuba lost all her children to war, or that a woman named Amiable once fondled a broken toaster oven? Probably not. More probable is that after a vicious war, the Trojan women of a destroyed civilization were subject to the whims and abuses of their male Greek conquerors. Thus Euripides’—and, therefore, our—play has a likely all-too-real, unfortunate historical basis. This is not just the stuff of myths.

--Jeff Stein

Welcome, Theater Lovers

In the best plays, the “suspension of disbelief” is produced involuntarily. Some theatergoers may work to subdue the natural, incredulous impulse—“that’s just fake blood,” “she’s not really dead,” “he’s ACTING,”—but, ultimately, it is the show’s responsibility to make an audience suspend its disbelief. When we go to a play, we want to immerse ourselves in the characters—to buy into an illusion we all know is patently false.

The theater company Hudson Warehouse has gotten and will continue to get audiences to do exactly this with Euripides’ The Trojan Women in June, Rostand’s Cyrano in July and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in August. Each weekend, these plays will work to make hundreds of people forget that they are at a play, and to therefore believe the joys, pains and tribulations of the invented people we call characters.

Yet this blog, however diminutive its scope and limited its ambition, will work against this goal. Through anecdotes, stories and interviews, I, along with fellow Production Assistant and old friend David Martin, will explore what the show will try to get you to forget. We’ll ask our actors what they really think about the people they pretend to be, reveal our director’s manipulation of ancient scripts, and, even, divulge our secret recipe for fake vomit.

So—whoever, if anyone, is out there—sit back and enjoy, gently to hear, kindly to judge, a blog about our play.

--Jeff Stein